Table of Contents

Landslides, mud flows, debris flows, and rockfalls are among many geologic and soil hazards that impact Colorado.

Landslides are the downward and outward movement of slopes composed of natural rock, soils, artificial fills, or combinations thereof. Common names for landslide types include slump, rockslide, debris slide, lateral spreading, debris avalanche, earth flow, and soil creep (Colorado Natural Hazards Mitigation Plan, 2013). Landslides move by falling, sliding, and flowing along surfaces marked by differences in soil or rock characteristics. A landslide is the result of a decrease in resisting forces that hold the earth mass in place and/or an increase in the driving forces that facilitate its movement. The rates of movement for landslides can be very quick (tens of feet per second) or very slow (fractions of inches per year). Landslides can occur as reactivated old slides or as new slides in areas that have not previously experienced them. Areas of past or active landslides can be recognized by their topographic and physical appearance. Areas susceptible to landslides but not previously active can frequently be identified by the similarity of geologic materials and conditions to areas of known landslide activity (p. 3-267 to 3-270).

Landslides are the downward and outward movement of slopes composed of natural rock, soils, artificial fills, or combinations thereof. Common names for landslide types include slump, rockslide, debris slide, lateral spreading, debris avalanche, earth flow, and soil creep (Colorado Natural Hazards Mitigation Plan, 2013). Landslides move by falling, sliding, and flowing along surfaces marked by differences in soil or rock characteristics. A landslide is the result of a decrease in resisting forces that hold the earth mass in place and/or an increase in the driving forces that facilitate its movement. The rates of movement for landslides can be very quick (tens of feet per second) or very slow (fractions of inches per year). Landslides can occur as reactivated old slides or as new slides in areas that have not previously experienced them. Areas of past or active landslides can be recognized by their topographic and physical appearance. Areas susceptible to landslides but not previously active can frequently be identified by the similarity of geologic materials and conditions to areas of known landslide activity (p. 3-267 to 3-270).

A mud flow is a mass of water and fine-grained earth materials that flows down a stream, ravine, canyon, arroyo, or gulch. If more than half of the solids in the mass are larger than sand grains—-rocks, stones, boulders—the event is called a debris flow. Debris and mud flows are combinations of fast-moving water and great volumes of sediment and debris that surge down a slope with tremendous force. They are similar to flash floods and can occur suddenly without time for adequate warning. When the drainage channel eventually becomes less steep, the liquid mass spreads out and slows down to form a part of a debris fan or a mud flow deposit. In the steep channel itself, erosion is the dominant process as the flow picks up more solid material. Any given drainage area may have several mud flows a year, or none for several years or decades. They are common events in the steep terrain of Colorado and vary widely in size and destructiveness. Extreme amounts of precipitation in a very short period of time (e.g., cloudbursts) and flash floods are the usual sources for creating a mud flow in Colorado (p. 3-268 to 3-270).

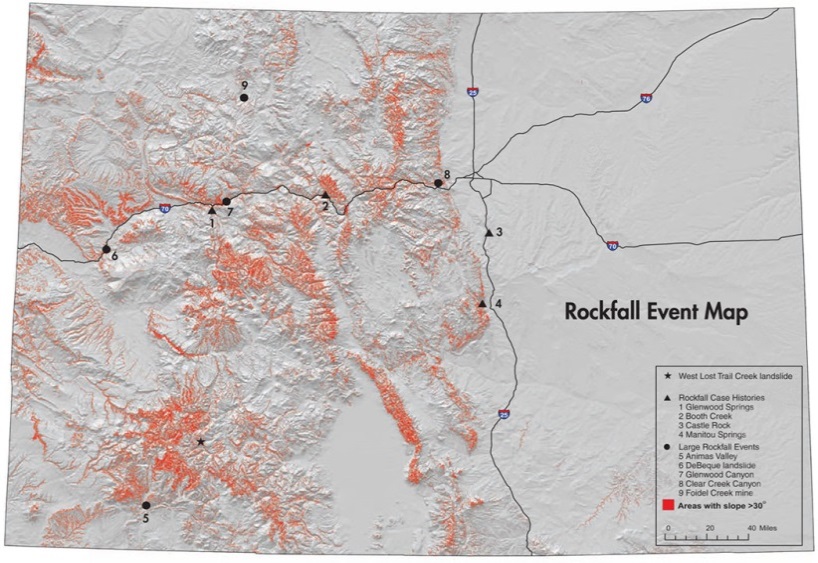

Rockfalls are a newly detached mass of rock falling from a cliff or down a very steep slope. Rockfalls are the fastest type of landslide and occur most frequently in mountains or other steep areas during early spring when there is abundant moisture and repeated freezing and thawing. Ice wedging, root growth, or ground shaking, as well as a loss of support through erosion or chemical weathering may start the fall (p. 3-269 to 3-270).

Land movement related to landslides, mud and debris flows, and rockfalls occurs naturally across Colorado on a continuous basis, and can also be triggered through human activity (primarily related to mining, land development, and other disturbances). These events can occur at any time of the year from almost any location along a slope; however, because they are correlated with elevation change, these hazards largely occur in the mountainous region from the Front Range to the West Slope.

Flash flooding or ongoing heavy rain can be precursors to landslides, mud/debris flows, and even rockfalls. Additionally, drought conditions may lead to soil compaction, and severe wildfire events may leave slopes denuded and hydrophobic. In these cases, a single heavy rain event can lead to higher volumes of runoff and correspondingly a higher risk for flash flooding, erosion, and especially mud/debris flows. Rockfalls are often caused by erosion of earth around larger rocks that then become loose and fall. Earthquakes can also lead to landslides and rockfalls.

Where landslides and/or mud/debris flows run out into stream valley bottoms they can cause temporary or even permanent blockages that may lead to Flooding and Fluvial Hazards such as erosion or sedimentation, channel migration or avulsion, and erosion of valley margins as the stream react to a sudden change in the configuration of the valley floor.

Nearly all geologic and soil hazards are highly localized events. The nature and extent of risk associated with each hazard is specific to local terrain conditions such as slope stability, vegetative cover, and geologic and soil composition beneath the earth’s surface. In fact, much of what helps determine the level of hazard risk at a precise location are the features and process that lie underground. Other factors include seasonal, climate, and weather-related phenomena (including other hazards) that can alter the local conditions that affect an area’s current risk. These variables make the identification, assessment, and mapping of geologic and soil hazards more difficult, especially for the purpose of designing and implementing planning tools or strategies. However, given the extreme danger these hazards pose, the knowledge and understanding of a site’s geology is essential in order to adequately plan, design, and construct a safe development.

Geologic hazards such as landslides, mud and debris flows, and rockfalls are sporadic and somewhat unpredictable; however, geologic studies can determine historic runs and existing movement in the earth suggesting movement is occurring or imminent.

Consultation with geologists and other experts familiar with local conditions is an important first step for local planners seeking to assess the risk of their community and specific areas that are susceptible to geologic and soil hazards. The CGS and other official sources can provide map information on levels of risk, past hazard events, and the probability of future events. More site-specific data and mapping, however, will need to be obtained through technical studies for specific areas of concern. Communities may opt to hire a consulting geologist or geotechnical engineer to perform this work, or require such expert studies as part of the local development permitting process.

Consultation with geologists and other experts familiar with local conditions is an important first step for local planners seeking to assess the risk of their community and specific areas that are susceptible to geologic and soil hazards. The CGS and other official sources can provide map information on levels of risk, past hazard events, and the probability of future events. More site-specific data and mapping, however, will need to be obtained through technical studies for specific areas of concern. Communities may opt to hire a consulting geologist or geotechnical engineer to perform this work, or require such expert studies as part of the local development permitting process.